Review: Blue Hours by Alison Acheson

Calgary, Freehand Books, 2025

This is a touching book that takes a deep dive into the complexities of grief. This article was originally published in The British Columbia Review on April 29, 2025.

***

Alison Acheson’s debut novel Blue Hours is an invitation to step into this liminal space, where grief transports a father and son into a state of flux. Acheson (Dance Me To the End: Ten Months and Ten Days with ALS) explores issues of mourning, fatherhood, and betrayal as she introduces us to parents Keith and Raziel, and their seven-year-old son Charlie. Married 17 years, Keith and Raz had a relationship that worked. Keith felt proud of choosing to stay at home to raise Charlie, working as a music reviewer turned dad-blogger while supporting Raz’s thriving career as a photographer. At the beginning of the novel, Raz has just died after a brief course of illness. The novel spans Keith and Charlie’s first year without Raz, and places the emotional action at the centre of Keith’s maelstrom of grief.

Set in Vancouver, Acheson’s novel begins with what seems to be a common bereavement narrative, meeting Keith and Charlie as they stand at the centre of attention at Raz’s funeral, dazed and just getting by. The scene is surreal, with an unending line of well-wishing grievers bestowing platitudes on father and son. Keith’s sorrow has him stunned and jumpy after the days in hospice and his wife’s death:

"An aspect of this time he would never have known was how raw life could feel, as if all the protectives that people had wrapped around their selves had fallen away, and there was too much to take in, not even necessarily good and ugly, but just there, in front of him."

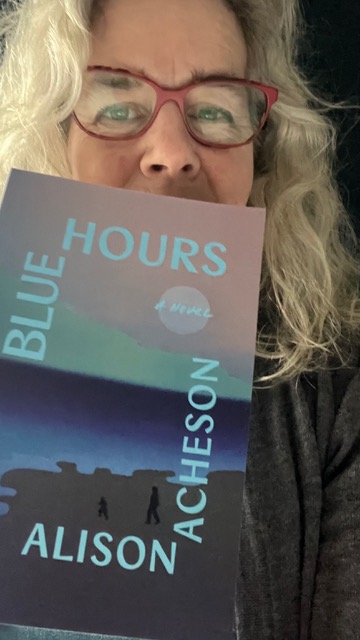

|

| Author Alison Acheson |

After the funeral, friends lend the pair a camper van, and Keith and Charlie set off on a road trip to visit Raz’s pregnant sister in Saskatchewan. The journey is a starting point for Keith and Charlie to reconnect, finding small moments of laughter and ways to remember Raz. Acheson introduces just a hint of the magical, an otherworldly nod to the mysteries of interconnectedness. Dreams hold some uncertain portent, and Charlie sees his mom’s spirit in a coyote, a motif that recurs throughout. Totems hold power: a truth stick, or a black rock that fits into Keith’s hand perfectly.

As their late-summer Saskatchewan sojourn ends, Keith and Charlie return to the city so that Charlie can start school, and Keith can get on with sorting through Raz’s effects. Here, the novel takes an unexpected turn as Keith uncovers secrets that Raz had deeply hidden. Vancouver resident Acheson doesn’t back away from the turmoil at this point, instead choosing to go all in with the jarring uncertainty that Keith suddenly feels towards his dead wife.

Blue Hours plumbs the depth of Keith’s psyche and struggle. He’s an engaging character, a down-to-earth man who loves his kid, loved his wife, and enjoys the company of friends and family. Raz’s death upends this, and as Keith realizes the extent of Raz’s deception, his sense of betrayal takes front billing. He questions everything, even how he defines his sense of self up to now given that the life he thought he was living may have been a lie.

This is where Acheson really delivers. She plays with the notion of seeing: how we see ourselves and others through different lenses. The novel shows us Keith’s internal life in satisfying detail. We see Charlie in bright relief as well, sharply focused as seen through his father’s eyes. He’s a pleasure to read about as he navigates his young boy emotions and explores ways of coping, including selective mutism.

In obvious contrast, Raz is seen indirectly, mostly from Keith’s perspective. What was sharp becomes blurry because of her secrets and lies. As the bereaved husband attempts to piece together a more accurate picture of his wife, we see Raz through her sister, her co-workers, her photographs, and her hidden journals.

This choice strengthens the reader’s kinship to Keith. He cannot ask Raz about her life directly. He cannot get and will never have the answers that he so craves. In an emotionally harrowing episode (during which I enjoyed listening to Radiohead’s “Karma Police” as suggested by the playlist that begins each chapter), Keith discovers truths that shake him, and redefine the nature of his grieving—

"His own mind was filled with images and words, and a messy, dirty pain, the kind that scores flesh where it binds. Like some work of clay. The pain he’d felt losing her had been simple, clean. He was recognizing that now. He wouldn’t have before. But now, as much as it had ached before, it had been a life-lived pain, the price for loving. There had to be some price for love….

.…Was it even possible to grieve someone you didn’t know? Now there was the rub of this distancing intimacy. When someone died it was supposed to be some closure, but this wasn’t. It didn’t feel like a beginning either. It was a wading into a rushing stream that would take him, smash his bones into a rock, and leave him. There’d never be answers. She’d left too much for him to sort."

As their late-summer Saskatchewan sojourn ends, Keith and Charlie return to the city so that Charlie can start school, and Keith can get on with sorting through Raz’s effects. Here, the novel takes an unexpected turn as Keith uncovers secrets that Raz had deeply hidden. Vancouver resident Acheson doesn’t back away from the turmoil at this point, instead choosing to go all in with the jarring uncertainty that Keith suddenly feels towards his dead wife.

Blue Hours plumbs the depth of Keith’s psyche and struggle. He’s an engaging character, a down-to-earth man who loves his kid, loved his wife, and enjoys the company of friends and family. Raz’s death upends this, and as Keith realizes the extent of Raz’s deception, his sense of betrayal takes front billing. He questions everything, even how he defines his sense of self up to now given that the life he thought he was living may have been a lie.

This is where Acheson really delivers. She plays with the notion of seeing: how we see ourselves and others through different lenses. The novel shows us Keith’s internal life in satisfying detail. We see Charlie in bright relief as well, sharply focused as seen through his father’s eyes. He’s a pleasure to read about as he navigates his young boy emotions and explores ways of coping, including selective mutism.

In obvious contrast, Raz is seen indirectly, mostly from Keith’s perspective. What was sharp becomes blurry because of her secrets and lies. As the bereaved husband attempts to piece together a more accurate picture of his wife, we see Raz through her sister, her co-workers, her photographs, and her hidden journals.

This choice strengthens the reader’s kinship to Keith. He cannot ask Raz about her life directly. He cannot get and will never have the answers that he so craves. In an emotionally harrowing episode (during which I enjoyed listening to Radiohead’s “Karma Police” as suggested by the playlist that begins each chapter), Keith discovers truths that shake him, and redefine the nature of his grieving—

"His own mind was filled with images and words, and a messy, dirty pain, the kind that scores flesh where it binds. Like some work of clay. The pain he’d felt losing her had been simple, clean. He was recognizing that now. He wouldn’t have before. But now, as much as it had ached before, it had been a life-lived pain, the price for loving. There had to be some price for love….

.…Was it even possible to grieve someone you didn’t know? Now there was the rub of this distancing intimacy. When someone died it was supposed to be some closure, but this wasn’t. It didn’t feel like a beginning either. It was a wading into a rushing stream that would take him, smash his bones into a rock, and leave him. There’d never be answers. She’d left too much for him to sort."

|

| Author Alison Acheson |

Instead of a well-defined path to healing–which is where I thought the novel was going–it became more a series of uneven stepping stones for Keith and Charlie as they move towards an uncertain future. At times this almost made the novel feel disjointed, but taken as a whole, it’s not. Rather, the episodic tone depicts the common reality of grief: not one state of being to overcome as much as a messy stumbling from one emotion to the next.

Acheson cultivates a fantastic sense of community that father and son build around themselves to help them through this awfulness. Grammy Moth, a neighbourhood elder who is also seeking connection, is particularly wonderful: “rail thin and ropey, all bones and tendons, and the bright print baggy jumpsuit was too much empty fabric. Her hair was grey and piled in some terrible way on her head, probably not cut in years.” She is “grey wrapped in colour,” and adopts Charlie as she soothes with her quiet wisdom.

Blue Hours shows in bright relief the challenge of grieving a person who you thought you knew, and realizing it may not be that simple. Perhaps Keith won’t get the answers he craves in the aftermath of Raz’s death, but there’s the chance to redefine his role as father and friend. Reading her journals, he begins to see himself more clearly:

"The words should make the ideas clearer, should shed light, from a shadowless point, and Raz was using other light, blue hour light, to colour her words into something maybe pretty. To her. She wanted to create. He just wanted to know. Black and white. Sun at midday. No more shadows."

In the fleeting hours that constitute the span of a life, can we capture the essence of the person we knew, or will they always be an enigma? Is the blue hour moody and melancholy, or is it a perfect peace as we start the day, or turn in for the night? Acheson’s novel suggests that it could be both, and that the uncomfortable, murky place that we sometimes inhabit in the midst of change can be a fine place to rest, and begin again.

Comments

Post a Comment