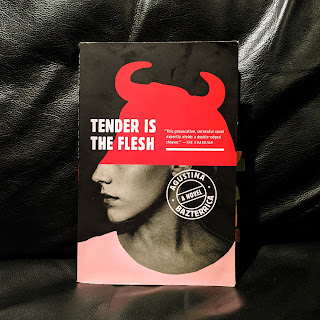

Review: Tender is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica

My Quick Take: I spent the first half of the book wondering if I should even be reading it, and the second half realizing how brilliant it is.

Translated from Spanish by Sarah Moses.

Note that this review may contain spoiler-ish material, though no overt spoilers.

***

This is a book that I’m not sure I can recommend to everyone. At the same time, it is so very meaningful. The text provokes inner dissonance. It is difficult, awful, sad, horrific and thoughtful, impactful, and rife with timely messages. It is the story of a world in which a virus has rendered all animals inedible, and the Transition has occurred to the legalized production, processing and eating of human meat. Not a spoiler, as this is on the back cover. That said, I didn’t read the back cover, and went in blind. Needless to say, I was taken aback. Like the literary equivalent of a car wreck, I wanted to look away, but couldn’t quite get myself to do so.

I spent a while wondering if I should even be reading this book. It felt illicit. Would people judge me for reading it? I suspect this is emblematic of my own self-censoring; it demonstrates how very taboo it is to even think or talk about cannibalism outside of the horror genre. In a straight-up horror novel or movie, the killer is aberrant, the antithesis of our social norms. They are depraved, feared and shunned. Ultimately they must pay for their heresy. Cannibalism is bad, and that is in harmony with our sense of self.

But in Tender is the Flesh, cognitive dissonance takes front and centre. Upright citizens are eating “special meat.” It is government sanctioned, and you’re suspect if you eschew eating flesh. If you say the wrong thing about the new practice, you can find yourself on the slaughterhouse floor. Cannibalism is good, encouraged, and a boon for the economy.

As readers, our guide to this future world is Marcos, who has lost his infant son, and whose grief-stricken wife has left him. He works for one of the most respected special-meat processing facilities. He is everyman, a stand-in for all of us as he holds this cognitive dissonance.

“He leaves the tannery and feels relief. But then he questions, yet again, why he exposes himself to this. The answer is always the same. He knows why he does this work. Because he’s the best and they pay him accordingly, because he doesn’t know how to do anything else, and because his father’s health depends on it.The discomfort comes in how flagrantly Bazterrica flaunts our taboo around killing humans for food and byproducts. She walks the reader through the entire process of what is involved in breeding, processing and eating “head,” as everyone in this new world must refer to them. Then she takes the whole thought experiment further, describing the uses of humans bred for meat in sport hunting and laboratory research.

There are times when one has to bear the weight of the world.”

Language plays a huge part in the story, and in Marcos’ understanding of the world and the people he encounters. Overtly, words and phrases are banned, like “human meat.” Any criticism of the policy is grounds for arrest. At one point, Marcos is visiting the tannery, the domain of one Señor Urami, who goes on and on about samples and skins, never once alluding to the fact that the product is human derived.

“Señor Urami’s words construct a small, controlled world that’s full of cracks. A world that could fracture with one inappropriate word…He knows he doesn’t have to say anything to this man, just agree, but there are words that strike at his brain, accumulate, cause damage. He wishes he could say atrocity, inclemency, excess, sadism to Señor Urami. He wishes these words could rip open the man’s smile, perforate the regulated silence, compress the air until it chokes both of them.”Marcos relates to others in the way they use language. He’s a bit of a synesthete, experiencing words as visuals, or physical sensations. Some people have, “light words, they weigh nothing.” The laboratory doctor’s words, “flow like lava from a volcano that doesn’t stop erupting, only it’s lava that’s cold and viscous. They’re words that stick to one’s body…”

In one particularly difficult section, Marcos must visit a trophy hunting reserve run by the darkly compelling Urlet, a man who made me shudder even as a reader.

“He thinks Urlet collects words in addition to trophies. They’re worth as much to the man as a head hanging on the wall…Urlet selects each word as though the wind would carry it away if he didn’t, as though his sentences could be vitrified in the air, and he could take hold of them and lock them away with a key in some piece of furniture, but not just any piece, an antique, an art nouveau piece with glass doors.”Later, they talk about the reserve’s hunter guests, and the nature of corruption, in a powerful passage.

“'There are people willing to do atrocious things for a lot less, cavalier. Like hunting someone who's famous and eating them.’The book shines a light on some dark corners of the human condition. It is entirely clear that this is a possible future where capitalism and greed have free reign. A need for the consumption of meat has been manufactured, and the masses have fallen in line. Veganism has been discarded as a viable option. Pleasure, overconsumption, and decadence are on full display. This contrasts with society’s disadvantaged: there’s a class of humans bred as a commodity, and another class of “scavengers,” who are the marginalized poor, shunned as the dregs of society. We see them through the eyes of the conforming middle class as undesirables and criminals.

…’Does this pose a moral dilemma for you? Do you find it atrocious?’ [Marcos] asks.

‘Not at all. The human being is complex and I find the vile acts, contradictions, and sublimities characteristic of our condition astonishing. Our existence would be an exasperating shade of gray if we were all flawless.’

‘But then why do you consider it atrocious?’

‘Because it is. But that’s what’s incredible, that we accept our excesses, that we normalize them, that we embrace our primitive essence.’”

This is not a rosy picture of human nature. It’s starkly apparent that in Bazterrica’s world, the strong-man politics of authoritarianism rules the day. It’s scary, because it hits close to home. How quickly we can accept a “new normal,” even if horrific. This is what happens in genocide: what is taboo one day is normal and encouraged the next. Even if this theme is seen in the kindest possible light, it shows how most of us might stay silent when faced with oppression, in the name of self-preservation. How we might silently accept a position of power over those who no longer have it.

It put me in mind of the famous quote from George Orwell’s 1984:

“But always–do not forget this, Winston–always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless.Perhaps slightly more controversial would be the question the book raises over eating non-human animals. If you simply look at the story as an allegory for eating cows, for example, or using their skin for leather, or drinking their milk, the whole thing seems pretty terrible. Perhaps this is a difficult message to accept because it hits closer to home in our world as it is now. As a society, many of us eat farmed factory meat, drink the milk of perpetually pregnant cows, and eat eggs from chickens in battery cages. We do it while never engaging with the animals that provide, while turning a blind eye. I do it too. And read in this way, we are all complicit.

If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face–forever.”

I stuck with this novel, and found it brilliant. I was sure I knew where the novel was leading me as a reader, convinced I knew what was going to happen, and that it wasn’t going to be pretty. I thought the inevitable but awful ending I foresaw would be a tribute to the core of decency in the human race, our collective humanity. [Slight spoiler alert] But no. The last chapter unfolded entirely contrary to my fanciful hopefulness. It was like a slap in the face by Bazterrica. It was as if, as a parting shot, she flipped us the bird and turned away from goodness. I get it, even if it seemed a bit of a cheap shot after stringing me along for the whole, appalling ride. After I sat with the ending for some time, I appreciated the clever cruelty in leading us along a path to possible sanity, then abandoning us to madness. It captures the ethos of the novel but man, oh man, was it depressing.

So, can I recommend this? Wholeheartedly…if you read to the end of this review and want to be challenged personally by a book that trips every known trigger warning, and leaves you feeling pretty awful. That’s the point, I think. By heeding Bazterrica’s warnings, perhaps we can wake up to the realities of power and exploitation, and try to steer our course towards compassion instead.

Comments

Post a Comment