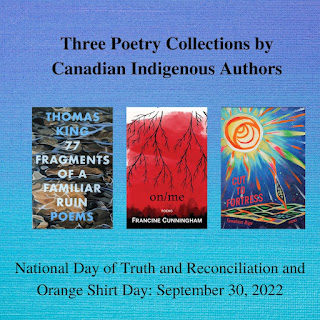

Three Poetry Collections by Canadian Indigenous Authors

September 30 is Canada's National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. "The day honours the children who never returned home and Survivors of residential schools, as well as their families and communities. Public commemoration of the tragic and painful history and ongoing impacts of residential schools is a vital component of the reconciliation process." (canada.ca). It is also Orange Shirt Day, which is "an Indigenous-led grassroots commemorative day intended to raise awareness of the individual, family and community inter-generational impacts of residential schools, and to promote the concept of 'Every Child Matters'. The orange shirt is a symbol of the stripping away of culture, freedom and self-esteem experienced by Indigenous children over generations" (canada.ca).

As King’s only poetry collection, this serves as an evocative introduction to some of his key ideas, many of which are quite dark. This poetry collection was an interesting way to get a concentrated version of King’s familiar themes. I might suggest paring this book with a listen to the 2003 CBC Massey Lectures featuring King, as they put the book in context.

Several themes were interwoven, but the idea of “story” was paramount for me. Using verse, he contrasted the Biblical and Indigenous creation stories; stories of the colonizer and the colonized; and even stories about ourselves that we are told by others, and tell ourselves. I came away contemplating how strongly the story of the dominant culture at any given point transforms history and current reality for so many of us. It makes me more determined to pierce the veil and see other stories and other points of view.

King uses much humour, but he wields it sharply as a tool of his anger. I'm not going to sugar coat it: this book is pretty bleak at times. Indeed, one of the most vivid poems for me used slaughterhouse imagery (swipe to see it in full). Coyote’s repeated visits to the doctor to get “diagnosed,” as a way to explain why bad things happen to him is darkly funny. Raven succeeds in getting themself elected as Prime Minister:

With this slim volume of poetry, the author allowed me an intimate and moving glimpse into her life. Cunningham's poetry collection strikes me as a memoir in verse: she gives us stories of her past, brings us to her present, and points in the direction of her future. She is an Indigenous artist and writer living a “literary artist travelling life,” visiting First Nations communities across Canada and teaching Indigenous youth.

On/Me is her ode to the many parts of herself and experience that reflect these truths, and she doesn’t shy away. There’s also some levity and a lot of warmth here, showing the utter humanness of her experience.

Reading this is like walking beside her. The opening poems are a stark introduction to her identity, family and illness. One poem I appreciated as a metaphor for her own mental illness was On Mental Illness/Fault Lines:

Finally, I feel her fatigue in struggle with the liminal, “Knowing that I will forever live here/in this space/of in between.” (From On Identity/Silence)

In the closing poems, Cunningham begins to see a way to accept this in-between-ness. It struck me as an acceptance of flux and uncertainty, and the necessity of living with the dialectics all of us face in different ways.

On Identity/Together:

This is a thoughtful debut poetry collection that took me from a sense of hopelessness to hopefulness.

I've been reading more Indigenous fiction, poetry and non-fiction in an effort to learn, re-learn and un-learn our collective history in North America, and it has been an enriching journey. Today, I wanted to highlight three Canadian Indigenous authors who have written poetry collections. I've read them all this year, and each has been so worthwhile.

Several themes were interwoven, but the idea of “story” was paramount for me. Using verse, he contrasted the Biblical and Indigenous creation stories; stories of the colonizer and the colonized; and even stories about ourselves that we are told by others, and tell ourselves. I came away contemplating how strongly the story of the dominant culture at any given point transforms history and current reality for so many of us. It makes me more determined to pierce the veil and see other stories and other points of view.

King uses much humour, but he wields it sharply as a tool of his anger. I'm not going to sugar coat it: this book is pretty bleak at times. Indeed, one of the most vivid poems for me used slaughterhouse imagery (swipe to see it in full). Coyote’s repeated visits to the doctor to get “diagnosed,” as a way to explain why bad things happen to him is darkly funny. Raven succeeds in getting themself elected as Prime Minister:

"It’s easy, says Raven.There is a sense of cyclicity to the book. After exploring so many of the “familiar ruins” that colonization has wrought, and that we all of us live amongst, one character, The Woman Who Fell From the Sky, assess the whole situation and says:

When no one is paying attention,

anything is possible."

"it would appear

we’re going to have

to start this story

all over."

With this slim volume of poetry, the author allowed me an intimate and moving glimpse into her life. Cunningham's poetry collection strikes me as a memoir in verse: she gives us stories of her past, brings us to her present, and points in the direction of her future. She is an Indigenous artist and writer living a “literary artist travelling life,” visiting First Nations communities across Canada and teaching Indigenous youth.

On/Me is her ode to the many parts of herself and experience that reflect these truths, and she doesn’t shy away. There’s also some levity and a lot of warmth here, showing the utter humanness of her experience.

Reading this is like walking beside her. The opening poems are a stark introduction to her identity, family and illness. One poem I appreciated as a metaphor for her own mental illness was On Mental Illness/Fault Lines:

“Waiting for the earthquakeA doorway is a threshold, a liminal space. I found myself contemplating liminal spaces while reading. She is constantly between. With mental illness, it is a dialectic between mania and depression; she is pulled between her White and Indigenous heritage; exploring her mother’s death, she shows how grief can be a liminal space of waiting and remembrance; and she contemplates her identity as a writer and the space between writing and not writing (“that hollow/that cavernous/space”).

is sometimes worse than the

earthquake itself”...

…“because what can I do?

you can’t patch the mantel

you can only prepare

for the rupture,

for what happens after

learn to stand in doorways

to avoid falling wires.”

Finally, I feel her fatigue in struggle with the liminal, “Knowing that I will forever live here/in this space/of in between.” (From On Identity/Silence)

In the closing poems, Cunningham begins to see a way to accept this in-between-ness. It struck me as an acceptance of flux and uncertainty, and the necessity of living with the dialectics all of us face in different ways.

"and maybe that’s the thingCut To Fortress by Tawahum Bige

everything that is me can’t be put into separate boxes

i can’t be spelled out in the blank space of a form

because I can’t separate the loneliness from the hereditary pain,

from the abuse, from the soul-leeching coldness of having no emotion,

to feeling like life is a dream

it’s all just me”

This is a thoughtful debut poetry collection that took me from a sense of hopelessness to hopefulness.

Bige is a Łutselkʼe Dene, Plains Cree poet who has performed as a spoken word poet, and has also been an activist, leading to incarceration in 2020 for their opposition to the Trans Mountain Pipeline. This is their debut poetry collection, and it is quite a read. There is so much that I assume is autobiographical. Throughout, Bige uses imagery of the natural world as a metaphor for innocence, and innocence lost.

In the opening poem Origin:

In the opening poem Origin:

"Tendrils, vines, root intertwine

and my connection is in the knowing

of parched paper, brushings of oak table.

Hardwood floors to thick tree trunk,

come into me, planet. Let me go back

to see the spruce that sprung the birch

that birthed me, the cedar that ceded my path

through trees of ash, maple, aspen. A pine cone

drops from its parent and I sense it fall

like a rock out of my pocket-I miss you."

There is a longing for the natural world and the past, as represented by untarnished nature. But soon Bige shows us layers that obscure that truth: colonization is symbolized by diseased flesh, modern industry and garbage. From Reasons to Decolonize:

The final two poems, Return Me and in time of war, are infused with hope, and a truly uplifting end to the collection:

"Gravel depositsMidway, the poem Too Abstract weaves evocative snapshots of colonization with a personal and tragic narrative. It is one of the most affecting poems of the collection, and the feeling-tone for me was hopeless and trapped.

Are sucked out the neck

Through industrial straws,

Filling out a parasite’s veins

Into roads across British Columbia

Built out of Annacis Island."

The final two poems, Return Me and in time of war, are infused with hope, and a truly uplifting end to the collection:

"no pedestal

a mutual acknowledgement

of our power and grace

our potential

let us rebuild this world together"

Comments

Post a Comment