Reading Women's History Month (or, Yes! It's another theme month!)

|

Before I started blogging and Instagramming about books and reading, I was aware that there were “theme” months, but only vaguely. Like, “Oh, it’s (insert theme here) month,” by way of media osmosis. They didn’t inspire my reading much. I didn’t not care, but theme months haven’t meant much to me personally. Happy they exist, but that’s the extent.

When you start paying attention to the book world, theme months hit you smack in the face. If you follow bookish social media accounts, or are on any publisher email lists, you cannot ignore their punch. So, March. It is most obviously Women’s History Month, or, more Instagrammishly: #WomensHistoryMonth; or acronymically: WHM. I suppose one of the questions I need to answer for myself is, how useful are theme months for me? Take WHM. Honestly, so much that I read falls into this category because: a) there’s a lot of history and b) half of the world is women. Just saying.

But…I find I do like the theme idea. Why? It becomes a device to focus my reading choices. It leads me to books and reading projects that I wouldn’t have thought of. It also demands a different way of thinking about the book in front of me: besides just being interesting, what is it telling me about how women have lived, been treated, or been mis-treated in a certain historical context. It is reading with intention.

Just when I got my mojo for WHM, an obviously more tuned-in Bookstagrammer posted their reading for Korean March! That’s right, another March theme. So, I chose two books to read for #KoreanMarch that also might fit WHM: literary double-dipping. I have yet to decide if they actually count for WHM, because they take place in the early 1980s. Is that history? Hmm…

[Brief digression: I got curious while typing this out…what other March themes might there be? A quick, imprecise Google search revealed a solid 17 themes on the first reliable-looking website I found. That’s reasonable. WHM was the first on the list. But then I noticed that Korean March was missing. Oh no. Back to the search results. Eventguide.com listed…wait for it…93. WHM was #13. #1 is National Sauce Month. There are many food months (most boring: National Flour Month), medical condition themes and pet-related themes. Some notable themes:

- National Mower Tune-up Month (note to self: must get my mower blades sharpened)

- National Umbrella Month (let’s all take a moment to remember our lost and broken umbrellas)

- International Mirth Month (we can all use a dose of this about now I’m sure)

- Mad for Plaid Month (in which I want to read a ton of Scottish Regency romances…)

- Play the Recorder Month (I don’t know who thought this was a good idea)

I think in April, I’m taking a break from themes. It is Poetry Month, and probably about 90 more. However, I’m going to make my own April theme called “A Little Light Reading Month” because I want to catch up on all of the fun, lighter books that I have sitting around on my TBR!

Without further ado, here is my list of WHM reading!

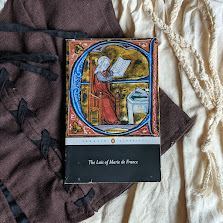

The Lais of Marie de France

Who might like these? Read these if you’re into a cool history lesson about an amazing female 12th century writer who writes entertaining and sometimes over the top tales of courtly love.

Bookish pairing: Matrix by Lauren Groff

I have to thank my daughter, a student of Mediaeval studies, for inspiring me to read the Lais of Marie de France. A lai is a lyric poem, often a love poem, designed to be sung to a popular melody, and was a feature of French Mediaeval life. Marie adapted the tales she’d long heard, probably after she had travelled from France to England. No one knows who Marie de France actually was, though she was probably an abbess and possibly the half-sister of Henry II. She was undoubtedly an educated woman familiar with court life, and may have written the Lais for Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine.I was amazed how absorbing 12th century female-written tales turned out to be! Marie sounds like a true character. In the preamble to one lai, she addresses the reader directly:

“Whoever has good material for a story is grieved if the tale is not well told. Hear, my lords, the words of Marie, who, when she has the opportunity, does not squander her talents. Those who gain a good reputation should be commended, but when there exists in a country a man or woman of great renown, people who are envious of their abilities frequently speak insultingly of them in order to damage their reputation. Thus they start acting like a vicious, cowardly, treacherous dog which will bite others out of malice. But just because spiteful tittle-tattlers attempt to find fault with me I do not intend to give up.”Well said, Marie!

I enjoyed reading these Lais so much. There are some fantastical ideas that captivated me! In Guigemar, a knight is cursed by a stag he has killed to suffer for love. A quest that includes a truly cool magical ship that sails itself ensues. In Bisclavret, a knight is trapped in his identity as a werewolf until he and his king outwit the culprits.

In this world, courtly love is one of the noblest concepts, and being truly in love is akin to a horrid disease that, if unrequited, leads to unforgiving torment. As Marie notes, “Love is an invisible wound within the body, and, since it has its source in nature, it is a long-lasting ill.” In one memorable description of a King who has fallen for the wife of his steward:

“Love admitted him into her service and let fly in his direction an arrow which left a very deep wound within him. It launched at his heart and there it became firmly fixed. Wisdom and understanding were to no avail…he was distraught and overcome with sadness. Unable to withstand its power, he was forced to give Love his full attention. That night he neither slept nor rested…”Ah, love!

Sometimes love is requited and all is wonderful. But, when knights and ladies harm other innocents in their pursuit of passion, beware! Things often end badly, and in a very over the top way. Guilty lovers are scalded to death in hot bath tubs, or have their noses eaten off (and then are destined to have children with no noses either…). Seriously harsh.

If you want something completely different in your reading life, try these Lais. They are short and entertaining to read, each Lais reading like a short story. Freely available on Project Guttenburg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/11417

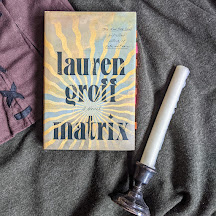

Matrix by Lauren Groff

Who might like this? Those interested in a feminist, queer imagining of the life of a Medieval nun, or interested in exploring tales of Medieval life.

Bookish pairing: The Lais of Marie de France

After reading some of my first Medieval literature with the Lais of Marie de France, I thought Matrix would be the perfect pairing. I bought it for my Medieval-studies-student-daughter's Christmas present! We both read it this month.

What I liked:

Groff’s imagining Marie’s visionary inspiration to build a community for women in a time where females were disempowered. In this era, physical beauty was akin to godliness, and Marie was a big-boned ill-featured woman who was sent off to an abby by Eleanor of Aquitaine, a stinging rejection from a Queen that she was in “courtly” love with. Marie turned the narrative on its head by empowering the women under her care, subverting the Church and embarking on a number of incredible projects to create a fortress, both literal and symbolic. The depiction of a community of women, all with their own foibles, who, despite dissent and hardship, developed wonderful bonds and created meaningful lives for themselves. The depiction of both platonic and erotic love here was genuine and became an integral part of the story.

What didn’t work for me:

After reading the Lais, I was ready for a deep dive into her process around writing and what it meant for a woman to have a voice in the Medieval world. I thought the Lais would play a bigger role. Alas, no. This is not the fault of Groff, but of my own hopes and expectations. Although the narrative moved well and the prose was crisp, I felt it a fairly superficial look at the character of Marie. I would have had the novel be longer to deep-dive into her relationships and inner life, and perhaps even to examine how her ideals, so at odds with the times, interfaced with the world around her. It felt more like a chronicle rather than an exploration. A well-done chronicle, but I think my expectations had a high bar.

A chronicle…like a lai…like Groff gave Marie her chance to write a longer, first person lai of her life…Wait, I think I’m overanalyzing this!

This may be one of those cases where I had such high expectations that the novel couldn’t help but disappoint slightly. Don’t let me put you off! Overall, Matrix was a totally worthwhile read, and paired nicely with some reading about the Medieval era and the Lais. As a package, this gave me a great mini-project for WHM.

Unwell Women by Elinor Cleghorn

Who might like this? Anyone with an interest in a whirlwind tour of how the patriarchal medical system has dealt with women’s “unwellness” and pain from the Greeks to modern day.

I paired this with a new podcast: The Story of Woman, which showcases “Interviews with authors exploring ‘man’s world’ through woman’s perspective.” The most recent episode featured Elinor Cleghorn’s book Unwell Women, and it was an interesting read. The podcast episode was fantastic.

The book delves into the history of “unwell women” from a medical perspective starting in ancient Greece and ending in the modern world. This was such an interesting read, full of wild and awful facts that show just how mistreated women have been over the centuries. I read it over the month and actually took notes, there were so many interesting bits.

The concept of “wandering wombs” beginning in Greek times was fascinating. Men declared that the uterus wandered around in the body causing all sorts of mischief, and the cure was intercourse, pregnancy or caring for children. This reflected the belief that a woman’s purpose was reproduction.

After anatomists figured out that the uterus was actually tethered, women’s emotions and pain were variously thought to originiate from disordered fixed uteri, the ovaries, the clitoris (that there was much female genital mutilation practiced in Victorian England shocked me), and eventually hormones. And with each medical advance, there generally existed an accompanying cure that harmed and degraded more than it helped.

Cleghorn took a difficult subject and acknowledged the inherent complexity. She did not just blame and shame, but often gave credit to forward thinkers of both sexes. Medical progress can empower women, but can also harm. Take the birth control pill. This gave women power over their own bodies and reproduction, but in its infancy was also tested in unwitting and impoverished research subjects; was advertised as “safe” when there were significant side effects; and was co–opted by the eugenics movement.

Progress occurred in fits and starts, and there’s no blame for that here. Physicians throughout history were simply at the limits of knowledge, and the guesses that they made seemed understandable much of the time. It wasn’t the attempt to explain but rather its use to subjugate and control that was devastating. Each bit of progress was overlaid with the lens of power and patriarchy.

She often featured how the intersection of gender and race compounded injustice.

Cleghorn has Lupus, and she finishes by examining some crucial issues over the last few decades. There is a thorough discussion of endometriosis, still underdiagnosed; and autoimmune disorders, which can be tricky beasts to diagnose, but affect women more than men. In the podcast, Cleghorn notes that medicine has always reflected the dominant cultural and social ideas, and even now, as we try to move to evidence based medicine, our attitude towards women is “imbued with sexist and misogynistic ideas,” and that to make progress we must, “separate myths…old stories from the objective, humanizing knowledge we need to properly care for people.” This book is a good starting place.

🎉 Bonus WHM reading if you think the early 1980’s are history-I’m going to say yes! This is also a two-for-one theme book for Korean March.

Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada

Who might like this? Graphic novel lovers or newbies who are interested in a college student’s experience under an autocratic regime in 1980s Korea.

I chose to read Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada, and illustrated by Ko Hyung-jo because I was searching up a graphic novel for WHM. I don’t often choose graphic novels, so I thought it might be interesting.

Apparently the novel is based on the author’s own experience and interviews with people who lived through the events, but to protect anonymity the stories were amalgamated into one and presented as one representative story. Hyun Sook has convinced her parents to let her attend college to study literature instead of working in the family restaurant in 1982 South Korea. She is drawn to a group of fellow students who meet to read banned books, and ultimately they rebel against a repressive regime. This political struggle comes at great cost to her and her friends.

I found the characters engaging. Hyun Sook truly had to overcome her reticence to rebel. She begins in ignorance of her own country’s situation, but wakes up to the injustice around her and fights for change. After she’s able to see things clearly, I love a scene when she confronts another student who is challenging her about banned reading. She says, “You gotta wonder. Do they ban books because they see danger in the authors, or because they see themselves in their villains?” Such a great line!

The book not only showed the students’ struggle, but also showed the misogyny and sexual harassment that women had to deal with. That said, it was quite amusing when the female students’ “women’s work” was actually making Molotov cocktails.

I learned about a piece of history that was entirely unknown to me: Korea’s Fifth Republic, from 1981-87 under military leader Chun Doo-hwan. After the previous dictator’s assassination, this regime was supposed to transition South Korea into democracy, but the pace was slow and citizens were outraged by the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, where between 200 and 600 people died. The book did a good job of introducing this era. So much of the struggle in 1980s South Korea is relevant now, with books challenged and banned throughout the world, and here in North America. At the end of the book, one character is looking back on the struggle. Someone asks:

Groff’s imagining Marie’s visionary inspiration to build a community for women in a time where females were disempowered. In this era, physical beauty was akin to godliness, and Marie was a big-boned ill-featured woman who was sent off to an abby by Eleanor of Aquitaine, a stinging rejection from a Queen that she was in “courtly” love with. Marie turned the narrative on its head by empowering the women under her care, subverting the Church and embarking on a number of incredible projects to create a fortress, both literal and symbolic. The depiction of a community of women, all with their own foibles, who, despite dissent and hardship, developed wonderful bonds and created meaningful lives for themselves. The depiction of both platonic and erotic love here was genuine and became an integral part of the story.

What didn’t work for me:

After reading the Lais, I was ready for a deep dive into her process around writing and what it meant for a woman to have a voice in the Medieval world. I thought the Lais would play a bigger role. Alas, no. This is not the fault of Groff, but of my own hopes and expectations. Although the narrative moved well and the prose was crisp, I felt it a fairly superficial look at the character of Marie. I would have had the novel be longer to deep-dive into her relationships and inner life, and perhaps even to examine how her ideals, so at odds with the times, interfaced with the world around her. It felt more like a chronicle rather than an exploration. A well-done chronicle, but I think my expectations had a high bar.

A chronicle…like a lai…like Groff gave Marie her chance to write a longer, first person lai of her life…Wait, I think I’m overanalyzing this!

This may be one of those cases where I had such high expectations that the novel couldn’t help but disappoint slightly. Don’t let me put you off! Overall, Matrix was a totally worthwhile read, and paired nicely with some reading about the Medieval era and the Lais. As a package, this gave me a great mini-project for WHM.

Unwell Women by Elinor Cleghorn

Who might like this? Anyone with an interest in a whirlwind tour of how the patriarchal medical system has dealt with women’s “unwellness” and pain from the Greeks to modern day.

I paired this with a new podcast: The Story of Woman, which showcases “Interviews with authors exploring ‘man’s world’ through woman’s perspective.” The most recent episode featured Elinor Cleghorn’s book Unwell Women, and it was an interesting read. The podcast episode was fantastic.

The book delves into the history of “unwell women” from a medical perspective starting in ancient Greece and ending in the modern world. This was such an interesting read, full of wild and awful facts that show just how mistreated women have been over the centuries. I read it over the month and actually took notes, there were so many interesting bits.

The concept of “wandering wombs” beginning in Greek times was fascinating. Men declared that the uterus wandered around in the body causing all sorts of mischief, and the cure was intercourse, pregnancy or caring for children. This reflected the belief that a woman’s purpose was reproduction.

After anatomists figured out that the uterus was actually tethered, women’s emotions and pain were variously thought to originiate from disordered fixed uteri, the ovaries, the clitoris (that there was much female genital mutilation practiced in Victorian England shocked me), and eventually hormones. And with each medical advance, there generally existed an accompanying cure that harmed and degraded more than it helped.

Cleghorn took a difficult subject and acknowledged the inherent complexity. She did not just blame and shame, but often gave credit to forward thinkers of both sexes. Medical progress can empower women, but can also harm. Take the birth control pill. This gave women power over their own bodies and reproduction, but in its infancy was also tested in unwitting and impoverished research subjects; was advertised as “safe” when there were significant side effects; and was co–opted by the eugenics movement.

Progress occurred in fits and starts, and there’s no blame for that here. Physicians throughout history were simply at the limits of knowledge, and the guesses that they made seemed understandable much of the time. It wasn’t the attempt to explain but rather its use to subjugate and control that was devastating. Each bit of progress was overlaid with the lens of power and patriarchy.

She often featured how the intersection of gender and race compounded injustice.

Cleghorn has Lupus, and she finishes by examining some crucial issues over the last few decades. There is a thorough discussion of endometriosis, still underdiagnosed; and autoimmune disorders, which can be tricky beasts to diagnose, but affect women more than men. In the podcast, Cleghorn notes that medicine has always reflected the dominant cultural and social ideas, and even now, as we try to move to evidence based medicine, our attitude towards women is “imbued with sexist and misogynistic ideas,” and that to make progress we must, “separate myths…old stories from the objective, humanizing knowledge we need to properly care for people.” This book is a good starting place.

🎉 Bonus WHM reading if you think the early 1980’s are history-I’m going to say yes! This is also a two-for-one theme book for Korean March.

Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada

Who might like this? Graphic novel lovers or newbies who are interested in a college student’s experience under an autocratic regime in 1980s Korea.

I chose to read Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada, and illustrated by Ko Hyung-jo because I was searching up a graphic novel for WHM. I don’t often choose graphic novels, so I thought it might be interesting.

Apparently the novel is based on the author’s own experience and interviews with people who lived through the events, but to protect anonymity the stories were amalgamated into one and presented as one representative story. Hyun Sook has convinced her parents to let her attend college to study literature instead of working in the family restaurant in 1982 South Korea. She is drawn to a group of fellow students who meet to read banned books, and ultimately they rebel against a repressive regime. This political struggle comes at great cost to her and her friends.

I found the characters engaging. Hyun Sook truly had to overcome her reticence to rebel. She begins in ignorance of her own country’s situation, but wakes up to the injustice around her and fights for change. After she’s able to see things clearly, I love a scene when she confronts another student who is challenging her about banned reading. She says, “You gotta wonder. Do they ban books because they see danger in the authors, or because they see themselves in their villains?” Such a great line!

The book not only showed the students’ struggle, but also showed the misogyny and sexual harassment that women had to deal with. That said, it was quite amusing when the female students’ “women’s work” was actually making Molotov cocktails.

I learned about a piece of history that was entirely unknown to me: Korea’s Fifth Republic, from 1981-87 under military leader Chun Doo-hwan. After the previous dictator’s assassination, this regime was supposed to transition South Korea into democracy, but the pace was slow and citizens were outraged by the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, where between 200 and 600 people died. The book did a good job of introducing this era. So much of the struggle in 1980s South Korea is relevant now, with books challenged and banned throughout the world, and here in North America. At the end of the book, one character is looking back on the struggle. Someone asks:

“Are you surprised that after all that, we still have to fight the same fights?”Wise words indeed, and relevant to all of my WHM theme reading for March 2022!

“Not at all. Progress is not a straight line. Never take it for granted.”

Comments

Post a Comment