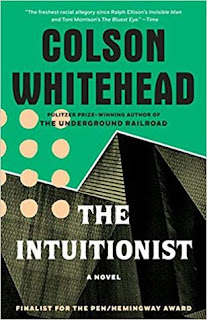

Review: The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead

Who might like this? Readers who don’t mind putting in some effort for the reward of a deeply interesting thought experiment. Elevators as a racial allegory is pretty compelling.

***

The Intuitionist, published in 1999, is American novelist Colson Whitehead’s first book. The premise is most interesting! In an alternate history, the Department of Elevator Inspectors ranks among the most influential city power brokers. Two main Elevation philosophies vie for power: the Empiricists, who believe in the traditional, hands-on way of elevator inspection; and the Intuitionists, who rely on feeling-sense to keep the city elevators running safely, a new way of doing things. After attending the Institute for Vertical Studies, protagonist Lila Mae Watson joins the Department as an Inspector, and the first Black woman to have the job. She is a staunch Intuitionist. She’s smart, fastidious and cautious, with a perfect safety record, until an elevator that she inspected crashes. She finds herself thrust into a shaky, fractured landscape that she has to navigate carefully, as she finds herself the scapegoat in an ideological war between Empiricists, Intuitionists, and corporate greed.

“Keep cool, Lila Mae,” the passively benign narrator says. It’s good advice.

This novel radiates a constant sense of threat and unease. The New York-esque cityscape is both squalid and aspirational, evoking an Orwellian visual in my imagination. Whitehead’s description of the city and its inhabitants is wonderfully evocative. As Lila Mae goes to inspect an elevator, “The light at this hour, on this street, is the secondhand gray of ghetto twilight, a dull mercury color.” There is an architectural tension in this city as the traditionalist “will to squat,” wars with “the seductions of elevators these days, those stepping stones to Heaven, which make relentless verticality so alluring.” Many of the characters are like paper cut-outs, but that just adds to the style of the novel. They are representational rather than real. Here, Whitehead’s descriptions continue to impress. Power-brokers are “a thicket of fedoraed men,” wearing, “remarkable pinstripes.” The Chair of the Elevator Guild is named Chancre, which is literally the word for a type of ulcer.

Lila Mae is written beautifully. She has such moxie and self-assurance that you trust she’ll be able to handle whatever awfulness the world throws at her, and there are some pretty awful things. She armours herself with a starched Elevator Inspector’s suit. She feels the constant threat of racism. She generally avoids the bar her co-Inspectors frequent, noting, “They can turn rabid at any second; this is the true result of gathering integration: the replacement of sure violence with deferred sure violence.” Hers is a struggle to take back agency in a world that wants to keep her a pawn.

On one level, this is a quirky alternate history, hard-boiled mystery about Lila Mae’s investigation into the elevator crash, in an attempt to clear her name. This leads her to discover deeper and darker motivations about the war between the Empiricists and the Intuitionists, and by extension, what it means to be a Black person in a world where race relations are increasing from a simmer to a boil. On this level, the novel is a bit slow for my liking. I found the pacing to be uneven, and the writing style and language took some effort to negotiate.

On a deeper level, however, this book is a racial allegory using the elevator as a metaphor for race relations. In this world, “getting vertical” equates to power, and everyone wants it. Whitehead takes no prisoners here, and all sides in this quest for supremacy are indicted to a degree. Institutions have their own agenda. This is truly where the undercurrent of violence lives: in the threat of aspirational elevator advancement to the status quo. The cool thing about Lila Mae is how she shows us that an individual can actually make a difference.

And sometimes, really fanciful notions poke their head through the narrative. Things about quantum physics, philosophy and sentient elevators. Much of this comes from the founder of Intuitionism, in his seminal book Theoretical Elevators…but I won’t say more! You’ll have to discover it for yourself.

I’m so glad that I read The Intuitionist. When an unjust system must change, elements in that system push back. At times, the book’s notion of “elevation” to a higher level of human collectiveness and justice seemed fraught with hopelessness, Lila Mae buffeted by the powers that be…who’s really pulling the strings of social justice? Do we–any of us–have hope of moving towards the lofty heights that Intuitionism promises?

If you give this novel your time and attention, it will reward you with a depth that is meaningful and satisfying, and not at all straightforward. As the author notes, “Verticality is such a risky enterprise.”

***

Favourite Quotes

“The falling elevator’s wake is sparks, thousands of them, raking the darkness all the way down.”

“She is mistress to her personality and well accustomed to reminding her more atavistic inclinations that the world is the world and the odd punch or eye-gouge will not make it any other way. It is rare that she felt this way, relishing violence. Very disturbing, however, this late business. It’s one thing to understand the muck of things, accept it, live in it, and quite another to have that muck change so suddenly and dramatically, to stumble down to a newer, deeper shelf.”

“What does the perfect elevator look like, the one that will deliver us from the cities we suffer now, these stunted shacks?”

“She did not feel she understood enough about Intuitionism to talk about it, no matter the extent of her sincerity. As if to speak out of turn would be the apotheosis of vulgarity, the most unseemly corruption.”

“Every room she enters lately is a cell…Each room is an elevator cab without buttons, controlled by a malefic machine room. Going down, no one else gets on, she cannot step off.”

“Time to sift the facts through her fingers and shake out the fine silt until what is left in her hand is what happened.”

“The walls are falling away, and the floor and the ceiling. They lose solidity in the verticality. At ninety, everything is air and the difference between you and the medium of your passage is disintegrating with every increment of the ascension. It’s all bright and all the weight and cares you have been shedding are no longer weights and cares but brightness…that last plea of rationality has fallen away floors ago, with the earth. No time, no time for one last thought…because before you can think that thought everything is bright and you have fallen away in the perfect elevator.”

Comments

Post a Comment